Unit 5 - Focus Groups

5.1 - Welcome to the Unit

Welcome to Unit 5 where we will explore the use of focus groups as a qualitative data collection method. A focus group is a group interview that usually follows a semi-structured format. Focus groups are a great way to foster debate and discussion between individuals with shared knowledge. However, interviewing several people together presents many challenges; these will be discussed in this unit. Despite the challenges, focus groups are opportunities for rich data collection which is enhanced through the discussion of multiple perspectives in a shared space. This makes focus groups a popular choice in qualitative studies. We will explore the strengths and limitations of focus groups. We will discuss face-to-face and online focus groups and provide practical advice on conducting both.Unit Content

→ Definition and description of focus groups

→ Group composition and sample size

→ Benefits and limitations of focus group approaches

→ Practical issues and advice for facilitation

→ Focus group interview schedules

5.2 - What is a focus group?

“A focus group discussion is a way to gather together people to discuss a specific topic of interest. The people participating in the focus group discussion share certain characteristics, e.g., professional background, or share similar experiences, e.g., having diabetes. You use their interaction to collect the information you need on a particular topic.” 1 (p.13)

The quote above by Moser and Korstjens1 explains that focus groups bring people together to discuss questions relevant to the research in a shared space. Focus groups can reveal insights into a topic in a way that might not occur in an individual interview. Principally, focus groups are a group interview usually conducted using a semi-structured format, so many of the semi-structured interviewing principles discussed in Unit 4 also apply to this method.

Participants in a focus group have been brought together because they have something in common in order to go beyond an individual perspective and toward a collective view. Of course, within this collective view there will still be areas of disagreement or divergent views – but this is exactly what focus groups want to examine.2 The range of viewpoints is an opportunity for rich, in-depth and complex data. How in-depth a focus group goes depends entirely on the interaction between members and the experience of the moderator to probe, prompt and invite responses.1 The aim of facilitation is to create a dynamic and interpersonal process.2

Focus groups can be considered a quick and convenient method of collecting data from several people at the same time.3 However focus groups should not be seen as a short cut where time and resources are limited. Focus group data is very different to interview data and so should not be used to answer the same research questions.

5.3 - Why use focus groups?

Focus groups are a popular method in health services research for their ability to determine views and perspectives on healthcare interventions and initiatives.4 They are a powerful tool where the emphasis is on the collective experience and the researcher places significant value in examining how this experience is verbalised between people in a shared space.This emphasis on the collective understanding is often (but not always) in contrast to the individual persepcive gathered during interviews, which usually examine how an experience or view is made sense of by that specific interviewee. Deciding whether to use a one-to-one interview or a focus group requires an evaluation of the benefits and limitations of each approach in the context of the research question(s) and the participants. For example, the research question may benefit from individual interviews; but if participants are more likely to talk when supported by others who share a common experience, then a focus group may be more appropriate. Focus groups are also frequently used during an exploratory phase of a multi-method study.4

| Focus groups are good for… | Focus groups are not good for… |

|---|---|

| Collective views. | Detailed life contextualised histories. |

| Support from peers. | Individual views. |

| Shared experiences. | Extreme views. |

| Different views. | Very heterogeneous participants. |

| Exploratory phase of a multi-method study. | Where there is a need for a high degree of control. |

Table 5.1: When to use / not use focus group methods.

Reflection Point

What do you think about the use of focus group approaches in neurosurgical research and what research topic may benefit from this method of data collection?

5.3 - Benefits and limitations of focus group approaches

No data collection method is perfect. Researchers must weigh up the benefits against the limitations in the context of the research question. The benefits and limitations of focus groups are summarised in Table 5.2. However, the flexibility of qualitative research means that in some studies, if one method does not appear to be working as expected, then the protocol can be amended (subject to ethical review) and the study will continue with a different way of collecting data to address the study aim.| Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|

| → May lead to a deeper understanding of the issues, both for participants and researchers. | → Can be tricky to maintain control of the discussion. |

| → Some participants may feel more at ease in a group setting. | → Can be difficult to record/transcribe – i.e. it may not be easy to identify who is talking, or to capture the non-verbal responses of other participants (e.g. nodding or shaking head). |

| → Can be empowering for participants. | → Some people may be reluctant to express views in a group (especially if they disagree with the majority). |

| → May save time and money compared to interviews. | → Can be difficult to get a range of participants. |

| → Can be fun! | → Can be difficult to organise dates, venues, etc. |

Table 5.2: Benefits and limitations of focus groups.

5.4 - Sampling and sample size

The rules of sampling from Unit 3 also apply to focus groups and demand a non-random, purposive approach. In addition, researchers must also consider both the number of participants and the number of focus groups: for example, 20 participants in two focus groups each lasting an hour will generate only two hours of data; compare this to five individual interviews each lasting two hours, which will produce 10 hours of interview data. Of course, the focus group data may be more complex, necessitating a more challenging analysis. But this illustrates the point that sampling is about more than just sample size. Issues such as time and resources must also be considered. So there are some pragmatic decisions to be made around sampling.

The researcher should also consider the potential influence of the size of a group: too few participants, and the discussion is hard to get going and maintain; too many, and the participants may end up talking over each other or arguing, or there may not be time for everyone to contribute. Typical size for a focus group is 6–12 participants,1 although other researchers suggest groups of between 4 and 8 participants.3 Smaller groups are better for more complex or sensitive topics where participants feel they have more time to share their experiences. Larger groups are better where participants’ common experiences are more likely to be similar or where less in-depth exploration of the topics of interest is needed (see Table 5.3).

5.4 - How long?

A focus group typically lasts longer than an individual interview – on average, between 90 and 120 minutes.1 This longer time is necessary to ensure that all group members can contribute, and because researchers also need to allow for brief introductions between participants to help them get to know each other and feel more comfortable. Time should also be allocated to a post-focus group debrief, which draws the session to a close prior to participants leaving. Anything longer than 120 minutes in total may risk fatiguing the participants. See Table 5.3 for some examples of time allocations within a typical focus group.| 6 participants | 12 participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-focus group | ||

| Welcome, introductions, ground rules | 10 minutes | 15 minutes |

| 90 minute focus group | ||

| Main question | 30 minutes total (5 minutes per participant) | 30 minutes total (2.5 minutes per participant) |

| Four follow-up questions | Approximately 12 minutes per question (2 minutes per participant) | Approximatley 12 minutes per question (1 minute per participant) |

| Summary and close | 10 minutes | 15 minutes |

| Post-focus group | ||

| Debrief and close | 10 minutes | 10 minutes |

| Total time | 110 minutes | 120 minutes |

Table 5.3: Example timings for a focus group (Table for illustration purposes only, this is not a rigid formula to be followed)

Table 5.3 illustrates that with a larger number of people attending the focus groups participants will have less opportunity to contribute to the questions asked.

5.6 - Group composition

It is important to think about who is invited to be part of a focus group. In order to encourage discussion and debate, participants should be selected who share something in common.4 Homogeneity is usually preferred in focus groups, unless the researcher is particularly interested in bringing together a heterogeneous group specifically to explore divergent views. The latter approach may be quite risky if there are power dynamics within the group that stifles discussion.3 For example, putting junior and senior neurosurgeons in the same group may marginalise the junior voices if they feel unable to disagree with the views of the senior neurosurgeons. In this case, it might be beneficial to conduct two focus groups, one comprising juniors and one made up of seniors. The differences and similarities can then be explored by the research team during the data analysis phase of the research.As well as the participants, there will be a moderator who takes the lead in asking questions and facilitating discussion of the group. It is also helpful to have an additional member of the research team present as an observer or notetaker who can complete the informed consent procedures, take detailed notes, record the dynamics of the group, and pay attention to non-verbal communication.

Key Points

Group composition→ Usually a homogeneous sample.

→ Heterogeneous groups only if required and risks are actively managed.

→ Moderator facilitates the focus groups, ask questions and steers the conversation.

→ Observer/notetaker assists the moderator.

Reflection Point

If you were designing a study about the working practices of staff in the neurosurgical intensive care unit, which staff would you invite? Would you conduct separate focus groups for each professional group or interview them together? Why did you make this decision?

5.7 - Managing a focus group

Conducting a focus group is often harder than conducting an individual interview, so a strong interview technique is required, which may benefit from practising with friends or colleagues. Bringing people together for the first time to discuss what may be quite an emotionally charged topic can bring out strong opinions and dominant views. While this exchange may be ‘rich’ in terms of data, discussions can snowball into something very difficult to manage and contrasting views may not be shared. In other groups, discussion may stall or not get going, and participants may find it hard to create any kind of dialogue.

Creating boundaries and ground rules can help in such situations. Common examples include simple agreements to: maintain confidentiality of participant contributions; respect each other’s views, even when these differ from one’s own; allow people the time and space to contribute; and not to talk over people. Although groups can still get out of hand, setting out rules at the beginning of a focus group can help to reduce the risk of this occurring and may encourage people to share their views because they feel they are in a safe space. Also, tell the participants what to expect – i.e. that the emphasis is on their discussion between each other. Start by allowing participants to ‘free flow’, take a back seat and watch the interactions and make notes on the discussion. Later, these notes can be used to probe the group and encourage the debate to continue.

Managing quiet members of the group can pose a challenge. While it may be tempting to manage this by allowing each participant a set amount of time to present their view and ask for these in turn, this isn’t in the spirit of a focus group, which draws its richness from the co-created discourse. However, it may be appropriate to invite a quiet group member into the discussion to allow them a specific opportunity to contribute. This can be done by noting a quiet participant’s non-verbal behaviour (e.g. smiling, nodding, looking surprised) and then asking the participant to share what they meant by these.4

During analysis of the focus group, it can be difficult to keep track of who was speaking when. Individual voices need to be distinguishable.4 This has led many researchers to video-record focus groups, so that when the discussion is transcribed it is easy to identify which participant is speaking. Another way to keep track is to ask participants to use each other’s names during the discussion and also refer to their own when they speak. Using name labels may be useful here. Make sure that if real names are used that these are pseudonimsed during the transcription of the focus group data.

Differences of opinion may be uncomfortable to observe, but resist the temptation to smooth these over. While you do not want this to build into an acrimonious dispute, divergent views are important to capture. If you need to intervene in a dispute, a more gentle way to address this situation would be to ask the participants if they can think of any reasons why they hold such divergent views.4 Remember that the role of the moderator is to facilitate the group and not to control it.

Extreme views or experiences can sometimes dominate a focus group. It is often more supportive to allow these stories to be told and then to gently re-focus the group onto the question being asked. Controlling the conversation too overtly can damage a participant’s confidence that you value their contribution, and they may be reluctant to contribute further.

Key Points

Managing a focus group

→ Adopt a strong interview technique.

→ Practise your technique using colleagues or friends.

→ Establish rapport (member to member, and member to researcher).

→ Create a safe space.

→ Set ground rules.

→ Resist the urge to tell your story.

→ Facilitate discussion, don’t control it..

→ Be aware and note non-verbal communication.

→ Manage dynamics, be inclusive.

→ Be aware of time, attention, fatigue .

| Practical considerations for managing a focus group |

|---|

| Create the right environment: Attend to things such as temperature, noise, privacy, wall displays/posters, appropriate refreshments, accessibility, and toilets. |

| Recording equipment: Make sure you have a functioning audio and/or video device, a backup device and spare batteries. |

| Note taking: Have a supply of A4 paper, pens and pencils, flip chart paper, board pens. |

| Assistance: Consider taking an assistant so that they can manage issues such as a participant becoming distressed or wanting to leave early. The assistant can also take notes on which person is speaking and specific body language displayed. |

| Name labels: Use name labels to help participants reference speakers by name (for ease of identification during analysis). |

5.8 - Online focus groups

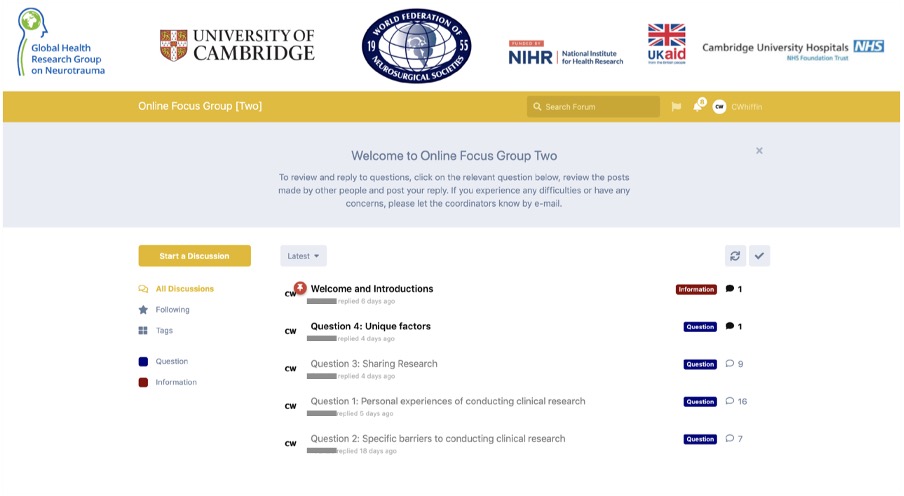

As discussed in Unit Four, online methods of data collection were already becoming popular for their convenience and flexibility. However, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically increased their use as researchers moved their data collection online wherever possible. While there is some hesitation regarding virtual qualitative methods, these can still elicit rich and meaningful data.5 Researchers can choose between a synchronous face-to-face method using a video calling app, or a synchronous or asynchronous online platform such as chat rooms.An example of an asynchronous online focus group used in a multi-phase study is Whiffin, et al.6(Figure 5.1). Participants were allocated to a focus group to explore five broad questions related to neurosurgeons’ ability to conduct and disseminate clinical research in low- and middle-income countries. The questions were designed to be exploratory and allowed participants to engage with each other and confirm if their experiences were similar or different. An analysis of this data led to the development of a semi-structured interview schedule, which was then used to examine the subject in more depth from an individual perspective.

Figure 5.1: Illustration of an online focus group data collection method.

Figure 5.1: Illustration of an online focus group data collection method.

If using online applications to store data, you will also need to check access rights and data protection.

NEURO_QUAL Podcast

Online Focus GroupsClick here to listen to Dr. Whiffin discuss the use of an online focus group prior to using semi-structured interviews.

5.9 - Creating a focus group schedule

Much the same as an individual interview, a focus group guide is a requirement of ethical approval and an important way of identifying the topics of interests related to your research question. However, given this is a group discussion which will generate more complex data, it may be prudent to have fewer questions than an individual interview and to increase the use of prompts, probes and invitations to group members to contribute to the discussion.Moser and Korstjens1suggest exploring topics of interest first, and then sequencing the questions in an appropriate order – with general questions appearing first, leading to more specific questions later. Positive questions also help participants relax in the early stages of a focus group, which may make people more able to answer more challenging questions toward the end of the group. All questions should be open-ended, simple and sound conversational. Invite dialogue by asking for examples and descriptions. Avoid ‘why?’ questions, which can sound confrontational if not phrased carefully, and avoid giving your own examples, which can be lead participants into reflecting your experience and therefore distort the data. Conducting a mock focus group is a good way of testing out the schedule and estimating the amount of time each question will take. This can also help improve your facilitation skills as you work through group dynamics and test out prompts and probes.

Key Points

Developing a focus group schedule→ This is required for ethical approval.

→ Use open questions.

→ Invite dialogue – e.g. ‘think back’, ‘can you give examples’.

→ Be wary of giving your own examples, as this can be leading.

→ Practise redirecting conversation..

→ Pose challenging questions to stimulate debate and discussion.

→ Be inclusive and use inclusive language.

NEUROQUAL Resource

Click here to download the focus group schedule resource.

Reflection Point

Think about how you might conduct a focus group with colleagues about their experiences of neurosurgical training. Who would you invite to the focus group, and what questions would you ask?

5.10 - Unit summary

In this unit, we have provided some practical advice on how to design and conduct a qualitative focus group. Focus groups are a useful tool for examining collective views from people who share a common experience. From a pragmatic perspective, where time is short, focus groups provide an excellent means of collecting data from several people at the same time, but this should not be the primary reason for their use. Focus groups can be challenging to coduct and require an experienced moderator; but facilitation skills can be learnt by observing focus groups that other people are facilitating, taking part in one yourself and by practising the skills outlined in this unit by undertaking a mock focus group.

References

1. Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9-18. doi:10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

2. Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation,. 2017;24(3):114-121.

3. Kitzinger J. Focus Groups. In: Pope C, Mays N, eds. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 3rd ed. Blackwell ; London : BMJ Books; 2006.

4. Barbour R. Doing Focus Groups. Sage; 2007.

5. Renosa MDC, Mwamba C, Meghani A, et al. Selfie consents, remote rapport, and Zoom debriefings: collecting qualitative data amid a pandemic in four resource-constrained settings. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(1). doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004193

6. Whiffin CJ, Smith BG, Esene IN, et al. Neurosurgeons’ experiences of conducting and disseminating clinical research in low-income and middle-income countries: a reflexive thematic analysis. BMJ open. 2021;11(9):e051806.