Unit 2 - Qualitative Research Design

2.1 - Welcome to the Unit

Welcome to Unit 2. In this unit, we will introduce you to the core characteristics of qualitative research and explain why it is relevant to the neurosurgical evidence base. We will outline some of the available research designs and common methods used to collect qualitative data. Some of this unit has been published in Whiffin et al.,1 ‘The value and potential of qualitative research in neurosurgery’.Unit Content

→ Definition of qualitative research.

→ Discussion of how qualitative research is important to the evidence-base.

→ Exploration of the breadth and scope of qualitative methodology.

→ Overview of qualitative data collection methods.

→ Introduction to sample size and sample types.

2.2 - What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a heterogenous research field. There are multiple definitions and multiple ways in which it can be conducted. 2,3 But while this heterogeneity causes some challenges to the field, there are broad principles that characterise qualitative research (for a critical discussion of what is qualitative research See Aspers and Corte 4). Qualitative researchers attempt to understand events and experiences through detailed descriptive and interpretive analysis of people’s experiences, views, perspectives and perceptions of their social reality. Most commonly (but not exclusively), qualitative studies use in-depth, non-numerical data collection methods to explore participants’ experiences.5 These methods can reveal important insights not possible from research using quantitative methods alone.6 There are many definitions of qualitative research, but a succinct definition is provided by Strauss and Corbin:6“… any type of research that produces findings not arrived at by statistical procedures or other means of quantification” 6

In contrast, Denzin and Lincoln2 add the characteristics of interpretive inquiry and meaning making of the naturalistic world.

“… qualitative research involves an interpretive, naturalistic approach to the world. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or to interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them.” 2(p.3)

A more recent definition is presented by Aspers and Corte 4 (see below) and this emphasises the process underpinning qualitative research and its intended outcome, which is to advance understanding of a phenomenon by getting closer to it. In this context, ‘moving closer’ can only be achieved by analysing first-hand experience.

“… an iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied”4

From these definitions we can begin to extract the important features of qualitative methodology, which in turn helps us to understand why, and in what circumstances, we would choose to use it.

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Non-numerical | Qualitative methodology is borne out of the understanding that not everything can or should be measured. In qualitative studies where there is some quantification of the data, these data must still be interpreted for what the quantification actually means. |

| Interpretive | Qualitative researchers do not have statistical formulae to decide what is significant within their data. Instead, they must rely on their own analytical skills to decide what is important. |

| Naturalistic | Qualitative studies are usually conducted about natural social reality. |

| Meaningful | Qualitative studies often want to understand how people make sense of events and experiences and what was important about these. |

| Iterative | An iterative approach in qualitative research is a process of systematic, recursive steps in which one moves forward and back using reflection to develop insight and deeper understanding of the data. |

Table 1: Characteristics of qualitative methodology

From these definitions, it is clear that qualitative research commonly uses approaches that are non-numerical, interpretive and iterative to make sense of naturally occurring social reality. However, qualitative methods can also favour description over interpretation, proceed in a linear rather than iterative fashion, include numerical data in its analysis, and be used to understand events that have been designed rather than occur naturally. Hence why a simple definition is incomplete and a comprehensive definition so elusive.

Key Points

What is qualitative research?→ A heterogeneous research methodology.

→ An attempt to understand the naturally occurring world.

→ Research that involves non-numerical interpretation.

→ Research that involves close interaction with the subject.

→ An iterative process underpinned by reflexivity.

2.3 - Why conduct qualitative research?

It is fair to say that qualitative methodology has been given less attention, and in some circles, less respect than quantitative approaches. Qualitative research has suffered from a label of ‘soft science’, which in turn has led to an assumption that it is not as valuable as ‘hard science’ associated with quantitative research. Therefore, qualitative research, and its contribution to evidence-based practice, has been viewed as less valuable than evidence generated through statistical measurement. However, research is about choosing the right methodology for the research question, and there are questions that simply cannot be answered, or answered well, if we do not commit to using in-depth methods that involve spending time with participants to understand their views and value their subjective experiences.

It is worth remembering that when we use descriptive and inferential statistics, we are often dealing with summary data and estimates of average values; moreover, ‘most is not all’, and statistical significance is not always meaningful to the lives of the population we are interested in helping. Measurement, and the resultant statistics, often give researchers a false sense of security and confidence in their conclusions. Yet if we know little about a concept at the start of a study, how can we be sure that we have the right tools to measure anything of value or importance to the population?

In contrast, qualitative researchers believe our lived experience cannot, or should not, be reduced to a simple count of observable features. Life, and our experience of living it, is about individual meaning and interpretation. Our lived experience is socially constructed, bound in our relationships with others, our cultural and societal norms, and shaped by both internal and external forces. These commitments support qualitative researchers to engage in inquiry that is in-depth and holistic.

Key Points

Why conduct qualitative research?→ Because a subject is poorly defined or understood.

→ Because a subject cannot or should not be measured quantitatively.

→ Because in-depth holistic inquiry will advance understanding.

→ Because context is important to the research question.

NEURO_QUAL Podcast

Why Qualitative Research is ImportantClick here to listen to a podcast from Dr Kathleen Khu about why she thinks qualitative research is important for neurosurgeons and neurosurgery.

Qualitative studies in neurosurgery are important because they examine topics that are not amenable to quantitative analysis and empirical measurement or where little is known about a subject area. In an editorial to the Journal of Neurosurgery, Khu and Midha 7strongly advocate for the contribution of qualitative research within medicine and healthcare, referring to the underpinning philosophy that medicine is an art as well as a science. Using the example of total avulsion brachial plexus injury, Khu and Midha 7 identify the benefit of research from the patient’s standpoint:

“The use of qualitative research in total avulsion brachial plexus injuries (BPIs) fills a void not addressed or explored by quantitative research. Clinicians are mostly concerned about treatment options and outcomes, but little has been written about the patient perspective of the disease […] it is imperative that we understand the condition from the patient’s standpoint to help them make informed decisions about their treatment.” 7

The studies listed below showcase examples of qualitative studies relevant to neurosurgeons. These studies all aim to explore, examine or understand an issue that is poorly understood or where gaining more understanding of contextual factors can advance practice:

Neurotrauma clinicians’ perspectives on the contextual challenges associated with traumatic brain injury follow up in low-income and middle-income countries: A reflexive thematic analysis 8

Attitudes toward neurosurgery in a low-income country: a qualitative study 9

Decision making among patients with unruptured aneurysms: a qualitative analysis of online patient forum discussions 10

The Impact of unmet communication and education needs on neurosurgical patient and caregiver experiences of care: a qualitative exploratory analysis 11

Motivations, barriers, and social media: a qualitative study of uptake of women into neurosurgery 12

Neurosurgeons’ experiences of conducting and disseminating clinical research in low-income and middle-income countries: a reflexive thematic analysis 13

Reflection Point

Think for a moment about why these studies were conducted using a qualitative approach and how knowledge generated in this way may advance neurosurgical practice.

Key Points

Why do we need qualitative research in neurosurgery?→ To examine experiences, perspectives and preferences.

→ To understand why a treatment is, or is not, effective.

→ To explore decision making and capacity.

→ To understand cultural, societal and contextual influences on care delivery.

2.5 - What are qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are usually broad and exploratory. These questions are particularly useful when a topic is under-researched or poorly understood. If a subject is not well understood, then it cannot be easily measured. This position of not knowing allows the researcher to feel freer to follow the data.

Qualitative research questions try to capture the essence of what it is the researchers are particularly interested in, such as: experience; context; culture or sense making. To answer such questions, researchers must be committed to analysing in depth and in detail.

Qualitative research questions are therefore commonly constructed around how, what and why. These styles of question reflect the exploratory nature of the investigation, which does not pre-suppose what the researchers will find out.

The following questions/aims are taken from recent qualitative studies listed above that are relevant to neurosurgery. The key descriptors are identified in red.

To understand the contextual challenges associated with long-term follow-up of patients following TBI in LMICs.8

To explore attitudes toward neurosurgery in a resource-poor setting.9

To understand the perspectives and experiences in medical decision making for patients selecting management for UIAs.10

To further explore neurosurgery patients' and caregivers' perceptions of the extent to which communication and patient education – preoperatively, during hospitalisation, and at discharge from hospital – met their needs and expectations.11

To explore how social media could be utilised to influence an individual’s motivation to pursue a neurosurgical career.12

To understand neurosurgeons’ experiences of, aspirations for, and ability to conduct and disseminate clinical research in LMICs.13

Reflection Point

Take a moment to think of a research question relevant to neurosurgery that could not be answered using a quantitative approach. How would this advance neurosurgical care?

Key Points

What are qualitative research questions?→ Broad and exploratory.

→ Focused on experience, context, culture and/or sense making.

→ Designed to elicit depth and detail.

→ Framed using HOW, WHAT, WHY.

2.6 - Qualitative research in medical journals

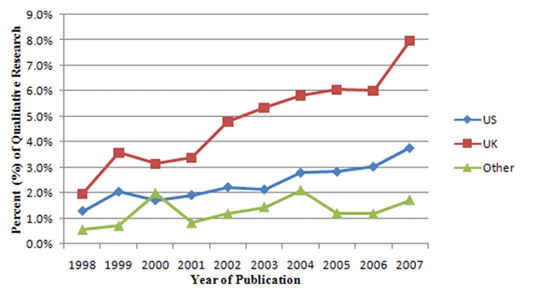

Medical journals predominantly publish quantitative research. Although there is evidence that medical journals are increasingly publishing qualitative research, rates remain low.14,15 Historically, qualitative research has been categorised with low-impact evidence such as case series, case reports, opinions and anecdotal findings. This may explain why qualitative research has not had an easy route to publication in medical journals.15 However, qualitative methodology is becoming more widely understood and its contribution to evidence-based practice more valued. Medical journals are, therefore, increasingly publishing qualitative studies for their ability to contribute to ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions that advance practice – as demonstrated by Shuval et al.14and their review of qualitative studies in medical journals, which illustrates a trend toward increasing publication (see Figure 1).

](https://neuroqual.org/v2/content/images/20240821145431-fig1.png)

Figure 1: Qualitative studies in medical journals by Shuval et al.14

There has been some heated debate about the publishing guidelines for qualitative research in the British Medical Journal; the BMJ had suggested that qualitative research was a low priority because it was unlikely to be cited highly or have practical value.16 However, more recently Retrouvey, et al.15 conducted a bibliometric and altmetric comparison of the impact of qualitative and quantitative research in the BMJ. They concluded that the 42 qualitative studies identified (out of more than 7,000 screened) published between 2007 and 2017 had equivalent impact to the quantitative articles:

“Our analysis reinforces the findings that qualitative and quantitative articles have similar academic impact.” 15 (p.6)

As already noted, while medical journals are increasingly publishing qualitative research, rates remain low.14,15 In neurosurgical journals specifically, there are even fewer examples.

Reflection Point

Why do you think that there is a lack of qualitative research in the neurosurgical evidence base? Do you think there should be more qualitative research in neurosurgery and if so what needs to happen to facilitate this increase?

Key Points

Qualitative research in medical journals→ Qualitative research is poorly represented in the medical literature

→ The publication of qualitative research in medical journals is increasing.

→ Qualitative studies have been shown to have a similar academic impact as quantitative studies.

2.7 - Methodological choice in qualitative approaches

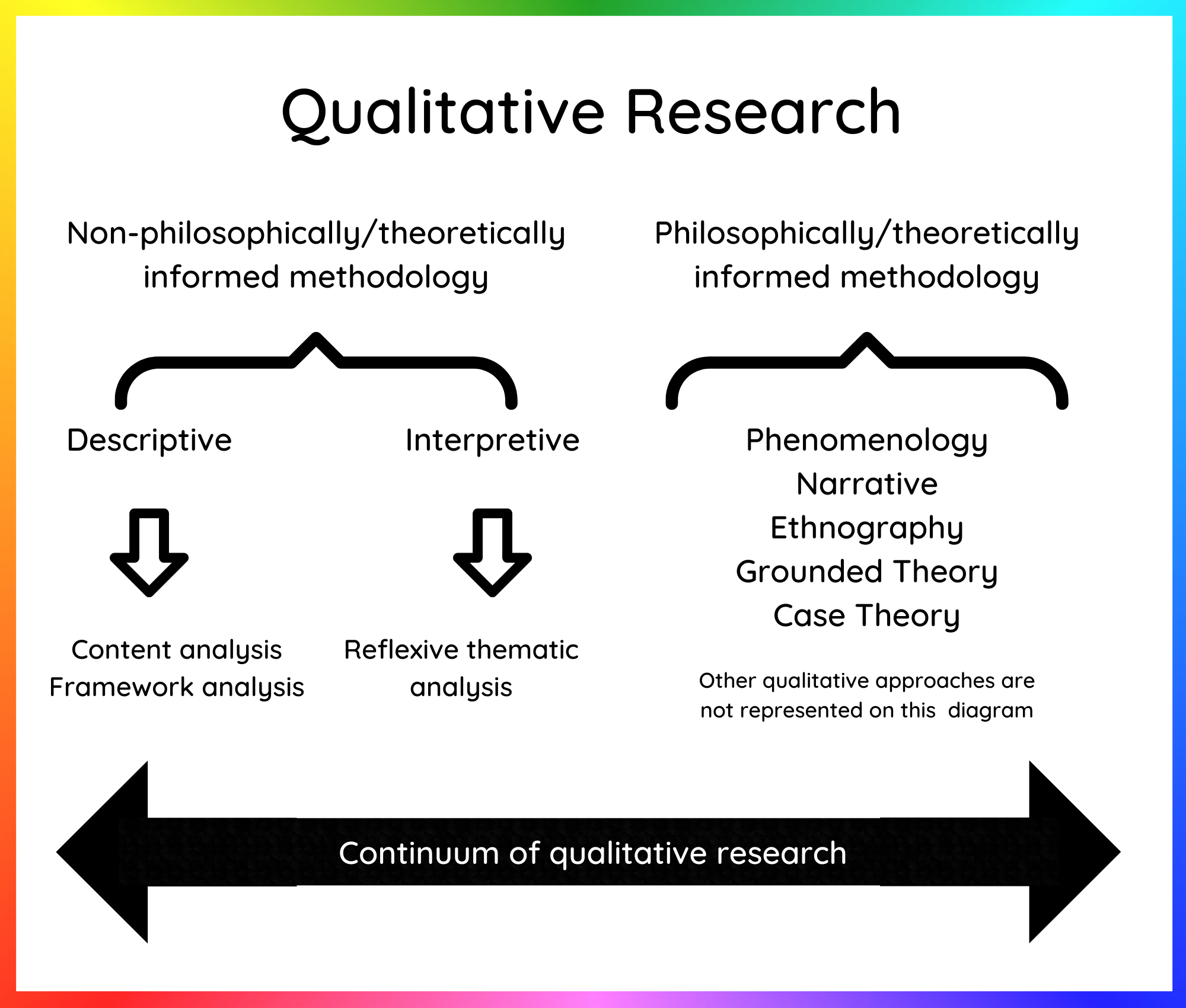

As a heterogenous field of inquiry, qualitative research has many research designs, which it may be useful to think of as a continuum (see Figure 2). This figure is a helpful way to think about the different approaches that are available, but many authors would reject such a typology for qualitative research because some methods simply do not fit. Nevertheless, for those less familiar with qualitative research this continuum can be a useful way to think about different ways to conduct qualitative research.

Figure 2: Continuum of qualitative research

NEURO_QUAL Podcast

The continuum of qualitative researchClick here to listen to a podcast from Charlie Whiffin explaining the continuum of qualitative research.

On the left-hand side of Figure 2 are thematic approaches most closely aligned to quantitative principles. As such, these studies tend to describe the patterns in the data through counting the presence of certain features of interest. Therefore, these studies often retain their foothold in [(post)positivist] assumptions and rely heavily on rigid procedures, coding frames, and inter-rater reliability of coding decisions.17 Examples include content and framework analysis; however, it is important to note that these studies can also adopt a more interpretive stance. Qualitative research designs on the left-hand side of Figure 2 do not have to be informed by philosophy or theory (although it is important to note that both Schwandt18 and Merriam19 maintain that research without theory is impossible, because no study can be designed without some influence or guiding interest, even if this is only implicit). Some studies using these methods simply report their study as ‘qualitative’ which can signpost the reader to a lack of philosophical/theoretical principles informing study methods.

A thematic approach described by Braun and Clarke20 is particularly popular and has been cited more than 90,000 times. However, Braun and Clarke 21 have suggested that their approach has been misunderstood and poorly used by many researchers. More recently, their approach has been defined as ‘reflexive Thematic Analysis’ (rTA) to emphasise the subjectivity and reflexivity which is central to its interpretive stance.21

Reflexivity has been defined as: The process of critical self-reflection about oneself as researcher (own biases, preferences, preconceptions), and the research relationship (relationship to the respondent, and how the relationship affects participant’s answers to questions). 22 (p.121)

Reflexive thematic analysis is situated within the centre of Figure 2 to illustrate its roots in the qualitative paradigm but also its freedom from specific pre-determined ontological and epistemological beliefs.17

NEURO_QUAL Podcast

Reflexive Thematic AnalysisClick here to a podcast from Dr. Victoria Clarke about Reflexive Thematic Analysis

On the right-hand side of the continuum are designs that have very specific ontological and epistemological anchors. These designs have particular ways in which the study should be designed and can support a more interpretive and/or in-depth analysis of meaning making. Such designs appear to be less commonly reported in the medical literature. Despite this these approaches are often (but not always) associated with more complex and sensitive analysis and so can take longer to complete. The ‘big five’ are: phenomenology, narrative, ethnography, grounded theory, and case study. However, there are many others, including discourse analysis, conversation analysis, and action research. While there are some commonalities between all these designs, there are important differences which set them apart (see Creswell and Poth23 for an extremely useful comparative text). Table Two summarises these designs and their main focus in addition to some common sub-divisions of the five main approaches to further emphasise the heterogenous nature of qualitative inquiry.

| Qualitative research design | Main focus of inquiry | Some common sub-divisions |

|---|---|---|

| Phenomenology | The essence of experience | Descriptive; interpretive; interpretive phenomenological analysis |

| Narrative | Exploring the individual life story | The ‘what’ of a story The ‘how’ of a story Biographical; life story; oral history |

| Ethnography | Cultural interpretation | Realist; critical; rapid; case study |

| Grounded theory | Developing theory | Classical; Straussian; constructivist |

| Case study | Examination of a bounded system | Intrinsic; instrumental; collective Collective; descriptive; explanatory |

Table 2: Comparison of five qualitative research designs and common sub-divisions

NEURO_QUAL Podcast

Qualitative Research DesignsListen here to podcasts from researchers about how and why they chose specific qualitative research designs:

Dr. Harry Mee chose Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to examine quality of life for patients following craniopasty.

Dr. Santhani Selveindran chose framework analysis to examine ways to reduce road traffic collisions in low- and middle-income countries.

Key Points

Methodological choice in qualitative approaches→ There are lots of different ways to conduct qualitative research.

→ Descriptive qualitative studies tend to base analysis on counts and frequency of data items within the data set.

→ Interpretive qualitative approaches favour interpretation and meaning of data items over frequency of these items within the data set.

→ Some research designs provide a specific framework for conducting qualitative research. These may be theoretically or philosophically informed. Most notably these are: phenomenology, narrative, ethnography, grounded theory, and case study. However, there are many others.

→ It is important to choose a research design that will answer the research question in the most comprehensive way.

2.8 - How should data be collected in qualitative research?

While quantitative studies often start from a position of knowledge and may be hypothesis-led, qualitative studies more commonly start from a more modest position of not knowing and thus being open to what they will find out. Qualitative researchers must spend time with the population of interest and ask them what they think, what their lives are like and what is meaningful to them. This is known as ‘inquiry from the inside’.

“I want to understand the world from your point of view. I want to know what you know in the way you know it. I want to understand the meaning of your experience, to walk in your shoes, to feel things as you feel them, to explain things as you explain them. Will you become my teacher and help me understand?” 24

The aim of qualitative data collection is to find out more about the phenomenon of interest. The best way to do that is to talk to, or observe, people who have direct experience of the phenomenon of interest. There are several different ways to collect qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, open ended survey questions, observations and secondary sources. However, the most common is the semi-structured interview.

Semi-structured interviews

Interviews are: “… a craft and social activity where two or more persons actively engage in embodied talk, jointly constructing knowledge about themselves and the social world as they interact with each other over time, through a range of sense, and in a certain context” 25 (p. 85)

The staple of qualitative data collection is the semi-structured interview. A semi-structured approach allows the researcher to have some control over what is discussed within the interview. This is particularly useful if you have narrower research questions which want to find out specific information. Like questionnaire development, the interview schedule should reflect the research questions and be developed from a contemporary review of the literature relevant to the topic of interest. However, in contrast to a questionnaire, the questions should be broad, open, and invite in-depth responses. In addition, you should set some probes, prompts and follow-up questions to help you get the most out of the interview. To learn more about qualitative interviews go to Unit 4.

Focus groups

Focus groups are: “a number of people collaboratively sharing ideas, feelings, thoughts and perceptions about a certain topic or specific issues linked to the area of interest” 25 (p. 83)

A focus group is an interview with a group of people held to generate discussion of issues presented by the researcher. Focus groups are particularly helpful when multiple perspectives are required and insight would be enhanced if these perspectives were shared and discussed between participants. To learn more about focus groups go to Unit 5.

Qualitative surveys

It is important to state that simply collecting qualitative data (i.e. non-numerical data) in a survey, for example, is not qualitative research if the qualitative data are to be analysed in a purely quantitative way – for example, simple frequency of recurring text. Some surveys will commit to a descriptive or interpretive analysis of open questions, but where the rest of the survey is predominantly quantitative people often limit their responses to open questions which in turn limits the analysis that is possible of these data.

In contrast, the are qualitative surveys which are from the outset designed specifically to elicit more in-depth responses with broader, more open questions. These are more representative of a qualitative commitment for in-depth data and can be analysed in more detail. Fully qualitative surveys are able to produce the sort of rich and complex data qualitative researchers seek to collect. 26 There is an assumption by some that qualitative surveys cannot yield rich information because of the lack of opportunity to probe participant accounts. Yet, in the right circumstances, to address appropriate research questions, qualitative surveys can be used to increase participation by those who would not want to be interviewed in person (e.g. those who would wish to stay anonymous).

Qualitative surveys also provide access to populations which are geographically dispersed and can be appropriate where the focus of the research is quite specific.26This latter point is demonstrated well in the study by Palmisciano et al.27 about attitudes towards artificial intelligence in neurosurgery.

NEURO_QUAL Podcast

Qualitative Surveys in Neurosurgical A.I. ResearchClick here to listen to Dr. Palmisciano about his choice of a qualitative survey to explore attitudes of patients and their relatives towards artificial intelligence in neurosurgery.

According to Braun et al.26 qualitative survey methods typically allow for larger sample sizes than face-to-face approaches and recommend piloting the survey and allowing time to amend/revise the questions as required. Caution is also advised for the length of the survey, as longer surveys increase the likelihood of non-completion. Therefore, less is more and keep to a few broad, topic based questions to encourage completion and richer responses.

Observations

Observational research is particularly helpful if you are trying to examine behaviours that people may not be aware of themselves or something that participants may find difficulty in disclosing. Benefits include examining life in ‘real time’ and aiding the development of contextual understanding of people’s lives.25 Studies of culture usually include some form of observational data collection so the researcher can immerse themselves in the setting and watch how people behave. These observations are recorded in detailed field notes.

Secondary sources

Collecting existing textual data and subjecting it to a qualitative analysis is an interesting and compelling form of qualitative inquiry. Increasing use of online blogs, chat rooms and social media mean there is an ever-growing corpus of data which could, under the correct ethical approval, be used to understand people’s experience in a way that lies outside the traditional research interview.

Visual methods

Going beyond traditional forms of knowing the world, visual methods represent the world in a way that isn’t written or spoken. Photographs, drawings and paintings etc. show (rather than tell) others what life is like on the inside. A particular method gaining popularity for its participatory method is PhotoVoice, which asks participants to share their lived experience through photography.28

Key Points

How should the data be collected?→ The aim of data collection is to find out more about the phenomenon of interest.

→ The researcher needs to choose a method that will provide data that is in-depth enough to answer the research question.

→ Qualitative data collection methods include: interviews, focus groups, open-ended survey questions, observations, secondary research and visual methods.

→ The most common method for data collection is the semi-structured interview.

→ Data collection methods must be balanced with the time and resources available to complete the study.

2.9 - Unit summary

In this unit we have introduced you to the principles of qualitative inquiry and how it can help advance the neurosurgical evidence base. We have explained that qualitative research is a diverse and expansive field which can facilitate an in-depth and rich understanding of people’s experiences. We have introduced the main approaches to data collection and signposted you to Units 4 and Units 5 where interviews and focus groups will be examined in more depth. The next unit will explore sampling in qualitative research and discuss data saturation.References

1. Whiffin CJ, Smith BG, Selveindran SM, et al. The Value and Potential of Qualitative Research Methods in Neurosurgery. Published online 2021.

2. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2005. Table of contents http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip053/2004026085.html

3. Saldana J. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. Oxford University Press; 2011.

4. Aspers P, Corte U. What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research. Qual Sociol. 2019;42(2):139-160. doi:10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7

5. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

6. Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research : Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications; 1990.

7. Khu KJ, Midha R. Editorial: Qualitative research in brachial plexus injury. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(6):1411-1412. doi:10.3171/2014.5.JNS141012

8. Smith BG, Whiffin CJ, Esene IN, et al. Neurotrauma clinicians’ perspectives on the contextual challenges associated with traumatic brain injury follow up in low-income and middle-income countries: A reflexive thematic analysis. Landenmark H, ed. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0274922. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274922

9. Bramall A, Djimbaye H, Tolessa C, Biluts H, Abebe M, Bernstein M. Attitudes toward neurosurgery in a low-income country: a qualitative study. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(5):560-566. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2014.05.015

10. Feler J, Tan A, Sammann A, Matouk C, Hwang DY. Decision Making Among Patients with Unruptured Aneurysms: A Qualitative Analysis of Online Patient Forum Discussions. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:e371-e378. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.161

11. Harrison JD, Seymann G, Imershein S, et al. The Impact of Unmet Communication and Education Needs on Neurosurgical Patient and Caregiver Experiences of Care: A Qualitative Exploratory Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:e1528-e1535. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.094

12. Bandyopadhyay S, Moudgil-Joshi J, Norton EJ, Haq M, Saunders KEA, Collaborative N. Motivations, barriers, and social media: a qualitative study of uptake of women into neurosurgery. Br J Neurosurg. Published online November 20, 2020:1-16. doi:10.1080/02688697.2020.1849555

13. Whiffin CJ, Smith BG, Esene IN, et al. Neurosurgeons’ experiences of conducting and disseminating clinical research in low-income and middle-income countries: a reflexive thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e051806. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051806

14. Shuval K, Harker K, Roudsari B, et al. Is qualitative research second class science? A quantitative longitudinal examination of qualitative research in medical journals. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16937. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016937

15. Retrouvey H, Webster F, Zhong T, Gagliardi AR, Baxter NN. Cross-sectional analysis of bibliometrics and altmetrics: comparing the impact of qualitative and quantitative articles in the British Medical Journal. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e040950. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040950

16. Greenhalgh T, Annandale E, Ashcroft R, et al. An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ. 2016;352:i563. doi:10.1136/bmj.i563

17. Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC, eds. Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. Taylor & Francis (Routledge); 2016.

18. Schwandt TA. Theory for the moral sciences; Crisis of identity and purpose. In: Flinders DJ, Mills GE, eds. Theory and Concepts in Qualitative Research. Teachers College Press; 1993.

19. Merriam SB. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; 2009.

20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

21. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019;11(4):589-597. doi:10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806

22. Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120-124. doi:10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

23. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. SAGE Publications; 2018.

24. Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview. Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1979.

25. Sparkes AC, Smith B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2014.

26. Braun V, Clarke V, Boulton E, Davey L, McEvoy C. The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2021;24(6):641-654. doi:10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

27. Palmisciano P, Jamjoom AAB, Taylor D, Stoyanov D, Marcus HJ. Attitudes of Patients and Their Relatives Toward Artificial Intelligence in Neurosurgery. World Neurosurgery. 2020;138:e627-e633. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.029

28. Halvorsrud K, Eylem O, Mooney R, Haarmans M, Bhui K. Identifying evidence of the effectiveness of photovoice: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the international healthcare literature. J Public Health (Oxf). Published online April 5, 2021. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab074