Unit 3: Qualitative Interviews

NEURO_QUAL Podcast Qualitative Interviews

3.1 Unit introduction

Welcome to Unit Three in which we explain how to conduct an interview for a qualitative study. In Unit Two, we introduced common qualitative methods and stated that the semi-structured interview was the staple of qualitative data collection; as such, it is the most popular way to gather in-depth data on the topic of interest. In Unit Three, we will describe different types of qualitative interview and explore their benefits and limitations for a qualitative study. We then consider some practical aspects of qualitative interviewing, including managing the environment, rapport, safety and managing recording devices. The unit concludes with a description of how to develop an interview schedule and some advice for enhancing the quality and richness of the data collected.

Unit Content: Qualitative Interviews

- Different types of research interview

- Practical aspects of qualitative interviewing

- Do’s and don’ts of qualitative interviewing

- How to develop a qualitative interview schedule

3.2 Types of research interviews

Reflect for a moment on the definition of qualitative interviews presented in Unit Two:

“… a craft and social activity where two or more persons actively engage in embodied talk, jointly constructing knowledge about themselves and the social world as they interact with each other over time, through a range of senses, and in a certain context” 1 (p.85)

What Sparkes and Smith are referring to in this quote is that qualitative interviewing is an active process. In this process, the participant and the researcher are jointly constructing the ‘data’. This data will be affected by a number of different internal and external factors from the interview schedule, the follow-up questions, the body language of both the interviewer and the interviewee, the environment, and the relationship and rapport established prior to, and during, the interview itself. Therefore, we can see that a qualitative interview should be more than just a means of extracting information from a subject in a passive and objective way.

There are three ways to conduct interviews in research: structured; semi-structured and unstructured. However, if we are cognisant of Sparkes and Smith’s definition and accept that qualitative interviewing is an active co-constructed process, then we should not consider using structured interviews. Structured interviews ask an interviewee a specific set of questions in a standardised, pre-determined order. Questions are usually close-ended or have limited response categories, which means they are inflexible and responses tend not to give sufficient detail. Structured interviews are more appropriate in quantitative studies where standardisation and consistency are key to reliability and validity.

In contrast, qualitative studies want to explore a subject in depth and in detail. It would be extremely difficult to gather such insights through fixed standardised questions, but semi-structured and unstructured interviews provide an opportunity for researchers to collect richer, more in-depth responses from their interviewees. See Table 1 for a summary of types of research interview. The following discussion will then explore semi-structured and unstructured interviews in more depth.

Table 1: Types of research interview

| Type of Interview | Characteristics | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structured | - Fixed schedule of questions - Questions asked in the same way to all interviewees - No deviation from the interview schedule - No prompts or probes - Easy to replicate and make comparisons - Inflexible - Responses lack detail |

N/A | N/A |

| Semi-structured | - Sits between structured and unstructured interviews - Schedule of pre-determined broad and focused questions - Probes, promp,ts follow-up and clarification allowed - Flexibility in question administration |

- Keeps the interviewee focussed - Provides a degree of consistency - Facilitates comparison between participants |

- Can limit the interviewee's responses - Schedules often designed with too many questions - Schedules may be followed too rigidily |

| Unstructured | - Interviewees will tell their stories freely with little interruption - Emphasis on informality and free-flowing exchanges - Focused on one or two broad topics - Questions are not pre-planned - Questions generated based on the interviewees' responses |

- Useful for gathering detailed information on complex issues - Greater flexibility - Good for building rapport with and empowering interviewees - Rich and complex data - Interviewee in control - Focused on what the interviewee wants to talk about |

- A lack of focus - A lot of data may be irrelevant to the research aim - Time consuming - Interviewee may find the lack of boundaries intimidating - Difficult to analyse and compare interviewee data due to non-uniformity |

3.3 Why use qualitative interviews?

The aim of this method of data collection is to examine experiences from an individual perspective for what they can reveal about the phenomenon of interest.

“at the root of … interviewing is an interest in understanding the experience of other people and the meaning they make of that experience”2 (p.3)

Individual qualitative interviews are a resource-intensive data collection method. Time is first required to conduct the interview, and then more time is needed to transcribe the interview and analyse the data. So if you do not have the time and resources available and your research project has tight deadlines, individual qualitative interviews may not be the right choice. Furthermore, if you already know a lot about a topic through a well-developed evidence base, it may not be worth investing time and resources interviewing people about their experiences. But if you have enough time and a particular research question that is poorly examined or poorly understood, qualitative interviews provide an exciting opportunity for interviewees to share their stories to empathetic listeners with an aspiration that their account will benefit others in the future.3

3.4 Practical aspects of qualitative interviewing

In qualitative interviewing, conversation is the central tool to gain information. Therefore, the context in which this conversation occurs is important, and consideration should be given to how the conversation can be improved to yield rich and meaningful data. The aspects discussed below will all affect the way an interview is conducted.

Power: Power is an important consideration in a research interview. If the interviewee feels that they have a passive role in the interview, that they are unable to deviate from the interview questions or that there are a defined range of ‘acceptable’ answers, then they are unlikely to share rich, detailed and contextual information. In the context of healthcare, the healthcare professional will be seen in many situations as having a significant amount of power over the participants, especially where the participants are patients or junior members of the neurosurgical team. Strategies to reduce the influence of this power should include a commitment to dispense with the notion that the interviewer is ‘all knowing’ and meet the interviewee as an equal who is more experienced and knowledgeable than the interviewer.

Rapport: Positive relationships are an essential component of qualitative interviewing because they affect the dialogue between the interviewer and interviewee.4 If an interviewee is relaxed, comfortable and feels they have more control, then they will be more likely to share information about themselves and their lives than if they feel intimidated, anxious or uncomfortable. Interviewees often relax as the interview progresses, so allowing enough time for interviews to be conducted properly is important. Having an opportunity to discuss the study and its requirements built into pre-consent meetings (i.e. before the interview) can also help build rapport.

Body language: In a research interview where the interviewer says very little, an emphasis should be placed on body language and eye contact. Both can reveal our inner thoughts on what the interviewee has shared. While staring a person in the eyes for 60 minutes would be inappropriate, asking questions while making eye contact and offering reassurance through eye contact shows interest and engagement.

The environment: Care should be taken to choose an appropriate room for the research interview. Select somewhere private and quiet where you are unlikely to be disturbed, or ask the interviewee to identify somewhere they would feel most comfortable. Think about the impact the environment may have on the interview. If the topic is about medical trauma, it may not be appropriate to conduct the interview in a clinical room in a hospital. Choose a layout that allows the interviewer to face the interviewee without any barriers (e.g. a table) between them. Make sure the interviewee can feel comfortable. It is for these reasons that often the participants choose the location of the interview, which may include their home.

Pen and paper: Don’t try to write down everything an interviewee says (this is why it’s recorded). But do make a few notes that can form the basis of probes and prompts later. Also, make a mental note and or write down significant body language or particularly important events so you can follow these up later. These notes are called field notes and will help later in the analysis.

Recording device: Make sure you have a reliable means of recording your interview and have practised with this prior to the interview taking place. There is nothing worse than realising the recording has failed after the interview has taken place. Many people also take a backup in case the recording equipment doesn’t work on the day. Also, take spare batteries or tapes if not using a digital recording device. You will also need to check the requirements of the sponsor or ethics committee in case the recording device has to be encrypted. If the interview is being held online, you can use the integrated recording feature of the video-calling application. You just need to check where the recording is stored and make sure access to it is encrypted. Discuss this with your sponsor.

Safety: As a lone researcher conducting face-to-face interviews, there may be risks associated with meeting people face-to-face. Inviting people into a medical facility can reduce this risk, but often qualitative interviews are conducted in people’s own homes. A risk assessment is important here, as is having a strategy in place to minimise this risk – for example, arranging to contact a colleague at an agreed time post-interview.

Be comfortable with silence: Silences in the interview can feel uncomfortable for the interviewer, but the interviewee may be using the silence to purposely construct what they want to say next, or they may simply need a moment to reflect on what they have just shared before moving on. Therefore, these pauses are actually very important in an interview dialogue. Resist the urge to probe or ask a follow-up question during these pauses. Wait to make sure the interviewee is ready for the next question.

Table 2: Practical tips for qualitative interviewing

| Feature | Top tip |

|---|---|

| Power | - Meet as equals - Approach the interview from a position of not knowing - Value the insights and experiences of the interviewee |

| Rapport | - Establish a safe and comfortable environment - Curate trust and respect - Value the information shared by the interviewee - Make sure there is enough time for the participant to relax into the interview - Use pre-consent meetings and the time prior to formal questioning to build rapport |

| Body langauge | - Use appropriate eye contact - Sit facing each other - Adopt an interested and engaged position |

| Environment | - Use a private, quiet room - Appropriate to context of the study - Remove any physical barriers - Make sure the environment is comfortable |

| Pen and paper | - Take notes selectively - Identify topics for later probes - Note non-verbal body language |

| Recording device | - Reliable - Safe - Encrypted |

| Safety | - Carry out a risk assessment - Have a procedure for escalating concerns |

| Silence | - Allow silence - Recognise natural pauses in speech - Look for phases that indicate account has finised, e.g. "that's it" |

3.5 Do's and Don'ts of qualitative interviewing

In Table 2, we have summarised some tips for the practice aspects of qualitative interviewing. Below, we offer some short do’s and don’ts to supplement that advice.

Do's:

- Give your whole attention

- Listen attentively

- Look interested and engaged

- Be prepared

- Be attuned to your fatigue and theirs

- Allow for silences and pauses

- Ensure you have allowed enough time

Don'ts:

- Don’t console

- Don’t give advice

- Don’t interrupt

- Don’t intrude yourself and your experiences

- Don’t try to do therapy

- Listen, don’t talk

- Never argue

Reflection Point

Think about how a qualitative interview may be different from a neurosurgical consultation.

What factors may help you to conduct a qualitative interview, and what may impede you?

3.6 Developing a semi-structured interview schedule

An interview schedule should be developed alongside the research protocol and will be a requirement of any ethical and or institutional review process. The interview schedule is more than a simple list of questions and should reflect the structure of the meeting with the interviewee. This helps the interviewer to feel confident about the process.

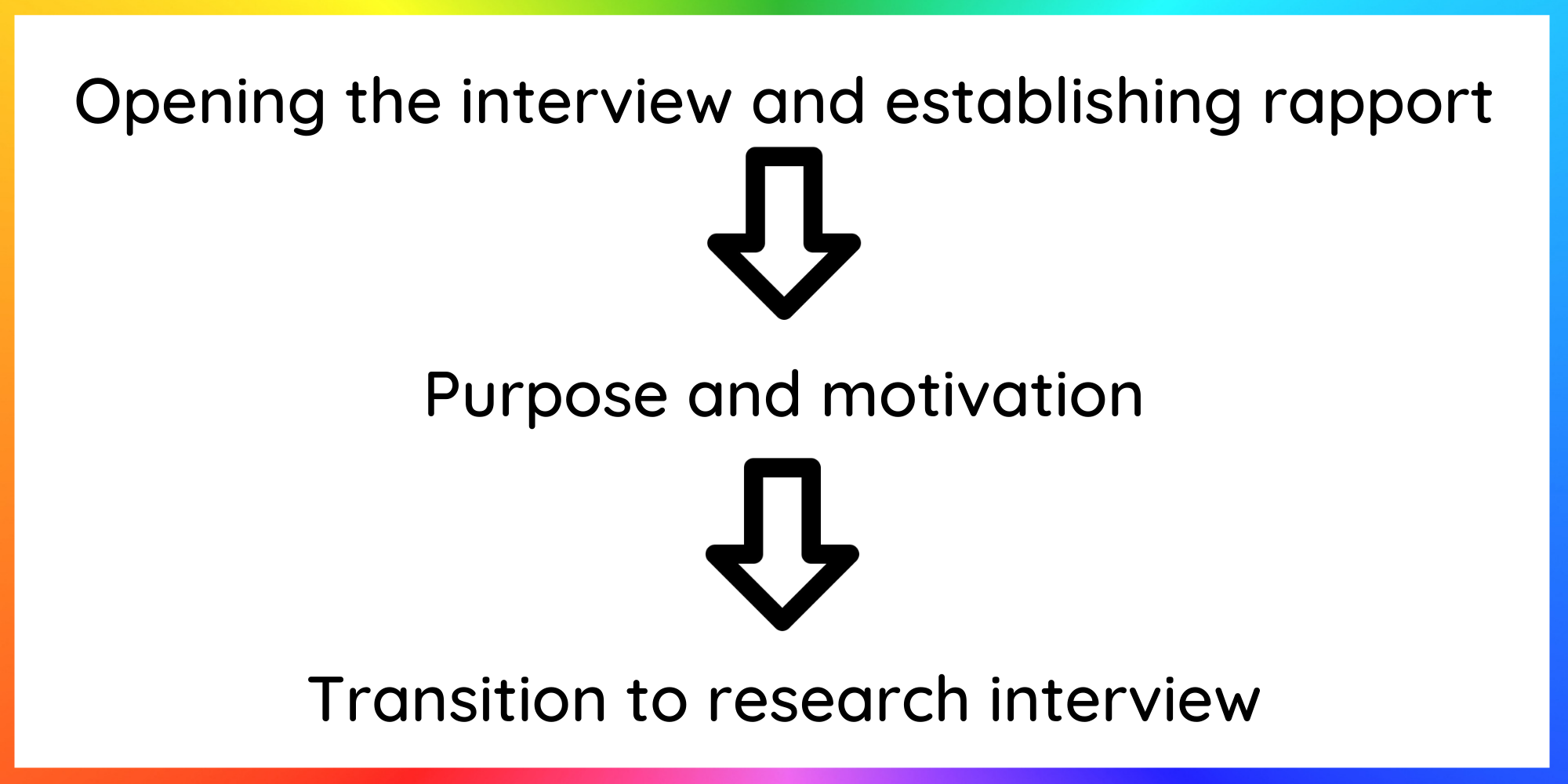

Pre-interview: As discussed earlier, the pre-interview exchange between the interviewee and interviewer is an important part of rapport development and will influence upcoming dialogue. There are three pre-interview phases (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pre-interview phases

Opening the interview and establishing rapport: This is the start of the interview process. It is important to be welcoming, open and honest. At this time, you can re-confirm aspects of consent, such as confidentiality, and that the interview can be stopped at any time. You may also invite any further questions about the study and what will happen during the interview.

Purpose and motivation: This second phase is to reiterate the context of the interview and what you will be exploring. You may want to remind the interviewee that there are no ‘correct’ answers and that you are interested only in their views and experiences. Tell them how long you expect the interview to last, and offer a short break if appropriate.

Transition to the research interview: In this final phase prior to the interview, confirm they are happy to proceed and tell them you will now start the recording.

The research interview: Once the recorder has started, you are now in the research interview and can follow your pre-determined schedule of questions. Developing a topic guide is important in a semi-structured interview and needs careful consideration so that the interview does not become aimless, meandering through any topics the interviewee wishes to discuss.5 Usually, the questions are developed following some engagement with the literature or/and a theoretical framework.

Interview schedules in most studies reflect the literature and what is already known on a topic or use constructs within a theoretical framework to guide question development. However, in classical grounded theory, researchers are asked to keep an open mind about the topic and therefore the literature review often takes place after data collection.

Researchers frequently design schedules with too many questions, often driven by a desire not to miss out anything important. Research interviews typically last 30–90 minutes6 so a schedule containing no more than 5–10 follow-up questions will probably be appropriate.4

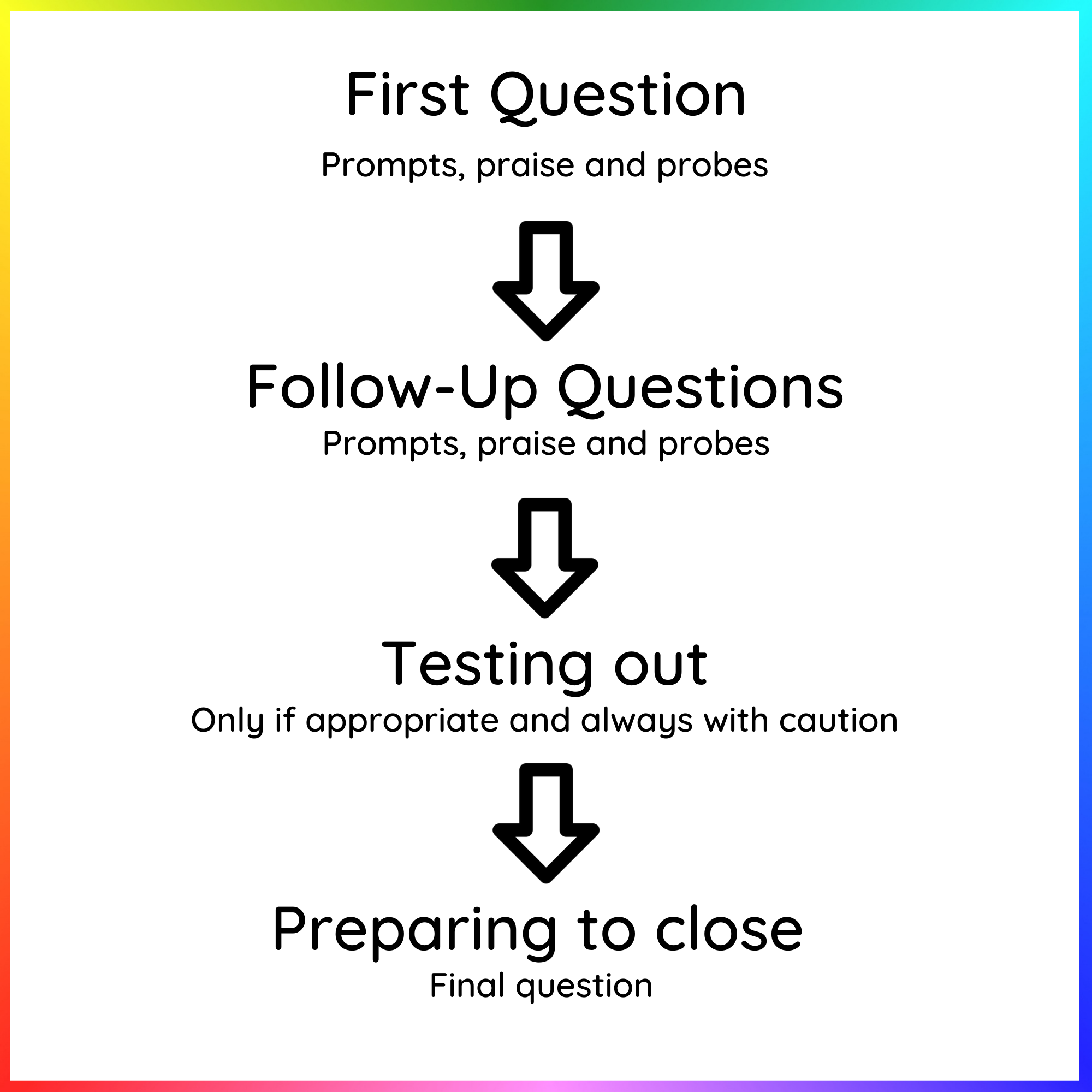

Figure 2: Phases of a semi-structured research interview

The first question: The opening question in an interview is extremely important. This question will frame and guide the subsequent dialogue. In some studies, the first question will simply reflect the main research aim, with subsequent questions aimed at more focused aspects of the research issue4 such as the research objectives. This broad question reflects its ambition to explore the topic widely from the participant’s point of view.6 Often, the interviewee will noticeably relax during this first question as they get more comfortable with their own dialogue and make decisions about what they want to tell you.

Praise and positive reinforcement: Being an interviewee can be quite intimidating. Participants may be anxious, nervous, or worried that they may say something wrong. It is therefore important to look like you are interested and engaged in their account. Being encouraging and grateful for responses can also put the interviewee at ease.

Examples of positive reinforcement

-

“What you said was very interesting, thank you.”

-

“It is very helpful that you explained it in that way.”

-

“I really appreciate your candor and honesty, thank you.”

-

“I can see that was a very difficult story to tell me, so thank you for sharing it with me.”

However, be mindful to use these phrases in a subtle and neutral tone that does not encourage the participant to focus their account on what you think is interesting. Wait to use these during a natural break in the account and before a prompt or probe instead of interjecting while the interviewee is talking.

Prompts and probes: After the opening question has been answered, the interviewer needs to be skilled enough to respond to the issues raised by the interviewee with prompts and probes. Prompts are questions to explore the interviewee account in more depth, while probes are words and signs that can be used to encourage the interviewee to say more.6 It is good practice at this stage to phrase prompts in the language used by the interviewee and in the same order they raised the points of interest. This attention to language shows that you are listening and helps not to distort the account or lead the participant toward the interviewer’s perspectives. This is especially important in the early phases of the interview. While the specific probes and prompts cannot be anticipated, it is possible to design a framework for these in which content can be added. This is particularly helpful to novice researchers who are not as skilled in their interview technique. Typically, probes focus on what and why questions first, moving to how questions later 6.

Examples of probes

- “And then what happened?”

- “When was that?”

- “When you said […] could you explain what you meant?”

- “You said […] why do you think that is?”

- “You spoke about […] could you tell me more about that?”

- “How did that make you feel?”

- “Could you help me understand why you felt that way?”

- “Could you give me an example so that I can understand this a bit more clearly?”

Examples of verbal prompts

Interviewee: "So, the other doctor was really blunt and said I wouldn't be able to have the operation ... I thought that was really rude"

Interviewer: "Rude?"

Interviewee: "Well, yes, he was rude because he just said it as a matter of fact while he was passing the bed, he didn't even stop to explain why"

Examples of non-verbal prompts

- Eye contact

- Leaning forward

- Open body langauge

Follow-up questions: As previously stated, subsequent questions are often more focused around what the researcher wants to know specifically and may be developed from the research objectives, the literature, a theoretical framework, or their own experience. In this respect, identifying the follow-up questions is somewhat like identifying the questions in a questionnaire. But unlike a questionnaire, the questions must be open, flexible and responsive to the emerging dialogue.6 In this regard, the interviewer can ask the questions in a different order, in a different way or not at all. For example, if an interviewee talks in-detail about a topic related to a pre-planned follow-up question as part of their response to the opening question, then it may not be necessary to ask the follow-up question, or it may need to be adapted to discuss the topic in a different way. Failing to be flexible and responsive in this way could lead to an interviewee feeling as if they are not being listened to, and this may affect their subsequent responses.

Testing out: In some research methodologies, it is appropriate to ‘test-out’ theories with interviewees, but in others this is not seen as good practice – so the interviewer will need to read around the research design they are following. Testing out theories or interpretation should always be done sparingly and with utmost caution, paying close attention to the interviewee’s verbal and non-verbal response. The aim is to summarise, not to add or distort.7 If included, testing out should always be done towards the end of the research interview so that the participant’s perspective is preserved as much as possible. The interviewer should supplement this interpretation with an invitation to confirm whether this interpretation is correct.

Examples of testing-out questions

- “So, I think to summarise what you were saying is […] would that be correct …?”

- “When you said […] do you mean …?”

- “Would I be right in saying that you felt […]?”

- “Thank you for that answer, would I be correct in saying that you were […]?”

Preparing to close: As well as starting well, an interview should also end well. The focus here is on making sure that the interviewee has had the opportunity to say all they originally wanted to and to signal that the interview process is coming to an end.

“… I have asked all my questions now, thank you for everything you have told me. We really appreciate you giving up your time to help us with this study. However, before we finish, is there anything else you’d like to add that you would like to talk about today?”

Post-interview: It is important then to consciously close the research interview and transition to post-interview debrief.

Close: Tell the interviewee that the recording has stopped, and ask them how they feel now the interview is over. If the interviewee found the process emotionally demanding, you may want to listen to their concerns, then signpost them to services that can offer support (these arrangements would normally have been pre-identified and would be listed in the participant information sheet used prior to consent). It is useful to explain what to expect next in the process, and then make sure the interviewee has your contact details before saying thank you and goodbye.

“I would like to say a sincere thank you for helping us with this study. We are enormously grateful to you. What happens next is that we will transcribe the audio recording and remove any personal details. Then we will then spend some time analysing your interview data and the data from other participants. In the meantime, if you have any questions or queries, feel free to email me. It was a pleasure to meet you, thank you again and enjoy the rest of your day.”

Video: Semi-structured inteview technique

🎥 Click here to watch a video demonstrating features of the semi-structured interview technique described in 3.6.

Template Semi-structured interview template

📝 Click here to download an example of a semi-structured interview template.

Reflection Point

Think about how you might conduct a semi-structured interview about childhood experiences of being ill.

What would you ask?

3.7 Developing an unstructured interview schedule.

Although ‘unstructured’ might seem to imply that a researcher can forgo the need for an interview schedule, this is not the case. The interview still needs to be planned meticulously so that the interviewer knows how to collect data in this method that will be relevant to the aims of the study. In this regard, there are still pre- and post-interview phases that should be planned and are important for rapport and putting the interviewee at ease. The first question is usually the only pre-planned question, so this question needs careful construction to help guide the interviewee on the area of research interest. In narrative inquiry, Wengraf8 calls this first question a ‘Single Question aimed at Inducing Narrative (SQUIN)’ – see example below:

“I would like you to tell me about your experience of working in neurosurgery … and all the events and experiences which are important to you personally … begin wherever you like… I’ll listen first, I won’t interrupt… I’ll just take some notes for after you’ve finished telling me about the experiences which have been important to you.” 8

The interviewer must then wait until the interviewee has finished responding to this first question before offering any prompts or probes. Remember that silence does not indicate the account is over, this may just be a reflective pause. Waiting for signals that the account has come to an end is crucial here, e.g. ‘that’s it’, ‘that’s all I have to say’, ‘I think I’ve covered everything now.’.

All subsequent questions then reflect the principles of the probes described earlier.

NEURO_QUAL Podcast Unstructured Interviewing

🎧 Click here to listen to Dr Tom Bashford talk about his use of unstructured interviewing to examine how clinical staff, patients, and other stakeholders articulate their experience of TBI care in Yangon General Hospital.

3.8 Unit summary

In this unit we have explained why and how to conduct a qualitative research interview and provided some helpful advice that will improve the quality of this exchange and as such increase the depth and richness of this method. We also cautioned against this approach if the study does not have capacity for the time and resources that individual interviews require. Where qualitative data is important, but time and resources are limited, a group interview, otherwise known as a focus group, may be more appropriate. How to conduct a focus group is explained in Unit Four.

References

-

Sparkes AC, Smith B. Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group 2014. ↩

-

Seidman I. Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. 3rd ed. ed. New York, N.Y. London: Teachers College Press 2006. ↩

-

Wolgemuth JR, Erdil-Moody Z, Opsal T, et al. Participants’ experiences of the qualitative interview: considering the importance of research paradigms. Qualitative Research 2014; 15(3):351-72. doi: 10.1177/1468794114524222 ↩

-

Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ 2006;40(4):314-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x [published Online First: 2006/04/01] ↩↩↩

-

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 2017;24(3):114-21. ↩

-

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract 2018;24(1):9-18. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091 [published Online First: 2017/12/05] ↩↩↩↩↩

-

Mayo E. The social problems of an industrial civilization. New York: MacMillan 1993. ↩

-

Wengraf T. Qualitative research interviewing: biographical narrative and semi-structured methods. Thousand Oaks, Calif.; London: SAGE 2001. ↩↩